Amazon is shutting down its fast, frugal, fledgling health care service, Amazon Care, at the end of this year. It was the fit that was faulty.

The company launched Amazon Care in 2019 as a pilot program for its Seattle-area employees before expanding to other employers in Washington and nationwide. The service incorporates a telehealth app, prescription delivery and the option to schedule a visit with a physician at patients’ homes and offices. In February, Amazon said it expected to roll out in-person services to 20 new cities this year.

Neil Lindsay, senior vice president for Amazon Health Services, told employees Wednesday the company had determined “Amazon Care isn’t the right long-term solution for our enterprise customers.”

“This decision wasn’t made lightly and only became clear after many months of careful consideration,” he wrote. “Although our enrolled members have loved many aspects of Amazon Care, it is not a complete enough offering for the large enterprise customers we have been targeting, and wasn’t going to work long-term.”

The announcement to end Amazon Care comes shortly after the company committed $3.9 billion to acquire One Medical, a primary care provider that has offices in Seattle and serves about 767,000 people nationwide. That deal is still subject to regulatory approval.

Lindsay said at the time Amazon saw an opportunity to improve the “quality of experience and give people back valuable time in their day.”

“Everybody wants to do health care and there’s a lot of inefficiencies in health care, so a lot of efficient companies think they can do better,” Jonathan Weiner, a professor of health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University, told The Seattle Times after the One Medical announcement. “Nobody would ignore Amazon in terms of possibly succeeding in those spaces.”

Amazon Care isn’t the company’s first failed health effort. The tech and retail giant was also part of a short-lived collaboration with JPMorgan and Berkshire Hathaway to improve health care costs. The three corporate giants formed an independent company called Haven to focus on improving care and manage expenses, but it dissolved last year.

“The closure underlines how hard making inroads into the health market is,” sad Neil Saunders, managing director at GlobalData Retail. “It serves as a warning that even with acquisitions, Amazon’s bid to shake up the sector will be incredibly difficult and possibly expensive.”

Last week, The Washington Post reported on tensions between Amazon Care and the clinical staff the company brought on to treat patients. Those medical professionals work for an independent company called Care Medical that is also being shut down. Six former employees said the two sides clashed over Amazon’s fast and frugal approach to expanding Amazon Care, which some former employees felt prioritized the business over best medical practice.

While planning to expand Amazon Care beyond Seattle, Amazon managers wanted to avoid building a physical hub. Instead, according to Washington Post reporting, they asked if nurses could store and dispose of medical supplies at home and stabilize patient blood samples using centrifuges in their personal care. The staffers protested the ask.

Thinking outside the box, or the exam room, was not unusual. Initially, Amazon Care clinicians saw patients on-site, at home and virtually, the former employees said. After the coronavirus pandemic began, visits included porches, garages and backyards. It became a popular option for Amazon employees seeking coronavirus tests and, later, vaccinations.

It was not immediately clear whether the overlap between One Medical, which serves consumers directly, and Amazon Care, which is an employee benefit intended in part to help companies lower health-care costs, led to Amazon’s decision to wind the program down.

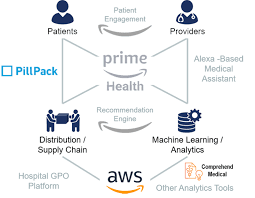

Amazon continues to operate Amazon Pharmacy, a prescription ordering and delivery service it spun out from its 2018 acquisition of Pillpack. Its cloud computing division, Amazon Web Services, also has a significant presence in health care, where it uses machine learning to analyze health-care data for large health organizations, among other enterprises.

Big Tech Struggles to Integrate Wellness and Innovation

Google attempted to enter the electronic health record playing field, but ended the program in 2011. The reasons cited for the failure were many.

One major issue was whether consumers could trust Google to handle their personal data, especially health data. A public embarrassment involved Google’s partnership with a chain of hospitals known as Ascension. In 2019, the news broke that some Google employees had access to Ascension patients’ private health information, as well as vast datasets of de-identified data. The news prompted a public outcry about the partnership, described internally as “Project Nightingale,” even though Google wasn’t doing anything particularly different from what health companies do all the time.

Another problem for Google was the lack of provider relationships. There weren’t enough third-party sources allowing patient data to be imported to Google Health. Google Health lacked relationships with big labs so consumers weren’t able to access their test results, which is one of the key attractions that often get patients using PHRs.

Microsoft shut down its line of personal mHealth apps, abruptly ending a program that sought to engage users in creating a digital platform for health and wellness. The initiative included a partnership with UPMC, a Microsoft Genomics program, the development of AI-enhanced health chatbot technology with partners like MDLIVE and Premera Blue Cross, and a software tool for radiotherapy planning called InnerEye.

But HealthVault Insights never really got off the ground, suffering engagement issues similar to those that plagued the personal health record movement in general. Critics noted the app platform went through at least two overhauls and didn’t offer much in terms of data support.

“We launched HealthVault Insights as a research project, with the goal of helping patients generate new insights about their health,” the company announced on its website. “Since then, we’ve learned a lot about how machine learning can be used to increase patient engagement and are now applying that knowledge to other projects.”

Apple’s moves in health have been modest. It has introduced apps to enroll people in medical research studies and software kits to make it easier for health developers to leverage health data. Its wearable device, the Apple Watch, is still more focused on helping people reach their fitness goals than on making a difference for people with medical conditions.

Former Microsoft executive: Dave Chase, a founder of Microsoft’s health business and now the founder and self-described heath care archaeologist of Health Rosetta wrote that the problem is a lack of truly integrated provider relations. “As much as there’s a massive consumer-empowerment movement, in order to get ongoing and broad adoption of something in healthcare, [tech companies] need to lead with the clinicians. Without provider adoption first, they will have limited success with consumers. [24×7]