Imagine if there were only 352,271 people left on earth. Like the elephant’s trumpeting cry, that critical number would signal a clarion call for action. Such a finding is the latest measure of the population of the world’s elephants in Africa, as monitored by Seattle’s Vulcan Technology.

Imagine if there were only 352,271 people left on earth. Like the elephant’s trumpeting cry, that critical number would signal a clarion call for action. Such a finding is the latest measure of the population of the world’s elephants in Africa, as monitored by Seattle’s Vulcan Technology.

The Seattle firm led by founder Paul Allen is developing solutions to track Africa’s pachyderms and protect the population againt attrition.

Vulcan built a state-of-the-art system for counting, storing, visualizing, and sharing census data, providing a powerful science-driven way to inform policy and the public about the nature and scope of the elephant poaching crisis. Why count elephants? Having accurate and reliable data about elephant population numbers is essential to form long-term conservation management plans.

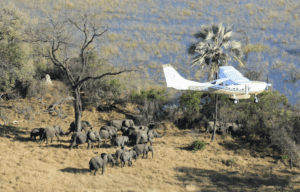

Vulcan’s aerial survey – the first in 40 years – covered nearly 345,000 square miles over 18 countries. Gathering high-quality data is vital, because it helps identify challenges and zero in on the most effective approaches to attacking them. This directly leads to better approaches in stopping the decimation of elephant populations.

• Savanna elephant populations declined by 30 percent(equal to 144,000 elephants) between 2007 and 2014.[2]

• The current rate of decline is 8 percent per year, primarily due to poaching. The rate of decline accelerated from 2007 to 2014.

• 352,271 elephants were counted in the 18 countries surveyed. This figure represents at least 93 percent of savanna elephants in these countries.

• Eighty-four percent of the population surveyed was sighted in legally protected areas while 16 percent were in unprotected areas. However, high numbers of elephant carcasses were discovered in many protected areas, indicating that elephants are struggling both inside and outside parks.

A handful of countries are doing a pretty good job of protecting their elephants, and their approaches can serve as models for other nations whose conservation efforts have been failing. Relative success stories include Botswana, South Africa, Uganda, Kenya, and the complex of parks spanning the border of Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin.

Elsewhere, in countries where poaching is still rampant, such as Tanzania and Mozambique, the survey’s alarming results have spurred officials to strengthen protections for their surviving elephants, and to crack down on the criminal networks that are driving the slaughter. Only time will tell, though, if they can arrest both the poachers and ivory smugglers and reverse the sharp decline of their elephant populations. Still, now that the scope of the problem is well documented, we know where to concentrate more resources and can become more effective in our approaches.

The Great Elephant Census is a collaboration between Vulcan and Elephants Without Borders, African Parks, the Frankfurt Zoological Society, theWildlife Conservation Society, the Nature Conservancy, the IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group and Save the Elephants, as well as a long list of conservation officials in the countries we surveyed. Many predicted such a Pan-African census was unlikely to succeed, if not altogether impossible. It required technological innovation, focus and unprecedented collaboration to bring the census to life. [24×7]

The Great Elephant Census is a collaboration between Vulcan and Elephants Without Borders, African Parks, the Frankfurt Zoological Society, theWildlife Conservation Society, the Nature Conservancy, the IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group and Save the Elephants, as well as a long list of conservation officials in the countries we surveyed. Many predicted such a Pan-African census was unlikely to succeed, if not altogether impossible. It required technological innovation, focus and unprecedented collaboration to bring the census to life. [24×7]