Seattle software savvy has opened up windows of productivity around the world. Our e-commerce vision has transformed the landscape of click-to-buy consumerism. Our gaming prowess has helped turn fantasy worlds and esports into virtual battlefields, and our trailblazing automation, from travel planning to real estate valuation, from genomics to life sciences, and from global philanthropy to artificial intelligence, are already making planetary impact.

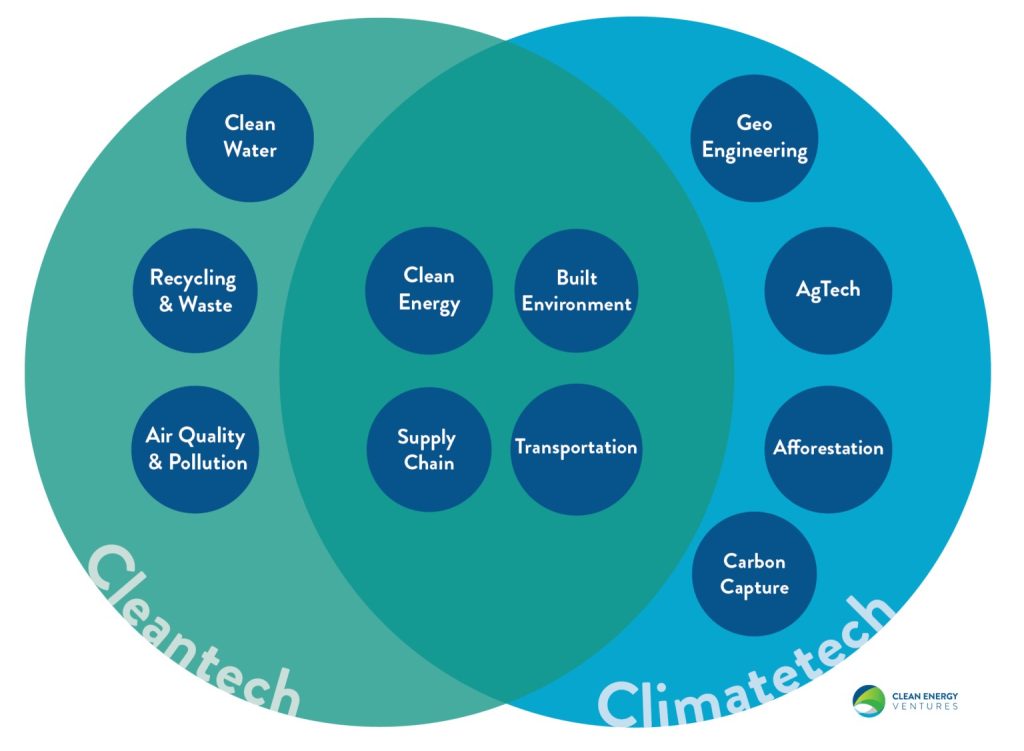

So can the Pacific Northwest’s entrepreneurial passion for imagining, investing, mentoring, funding, marketing and managing technological innovation solve the existential threat that climate change crises have wrought?

Who better than the inhabitants of an ecosystem where land and sea have melded together and the sky retains atmospheric rivers that pour down on a habitat where eagles, whales, salmon and people cohabitate under the shadow of an active volcano? Where else can the citizenry congregate in a revolutionary sports complex backed by Amazon and named Climate Pledge Arena, that pledges the goal of becoming a true, zero-carbon-footprint?

Watching where Amazon is investing is one way to track innovation in the space. It can also give investors a sense of what parts of its own business Amazon intends to prioritize in the future.

In September 2019, Amazon announced it was going to purchase 100,000 electric delivery vehicles from Rivian Automotive. Those vans are to be deployed by 2024 and are part of Amazon’s effort to convert its delivery fleet to 100% renewable energy by 2030.

Rivian transcends all other climate tech companies when it comes to venture capital dollars raised— over $8.9 billion in venture capital to date, more than any other climate tech company. In second place, raising half as much investor capital, is Sweden-based Northvolt with just over $4.4 billion.

As part of its electrification push, Amazon has also invested in Resilient Power, which is developing technology that builds electric vehicle charging infrastructure at one-tenth the size and installation time of existing charging technology.

“It’s Always Day One” To Plan for the Future

Matt Peterson is the head of The Climate Pledge Fund at Amazon: “A lot of what we invest for is three to five years out. We try to look around corners to see where our needs are going to be and where the needs of other companies are going to be. I mean, with with a 2040 time horizon, you know, you can’t really afford to look one or two years out, you have to think long term.”

The Climate Pledge Fund, which was announced in June 2020, is funded entirely with money from Amazon’s own balance sheet. For Amazon, the priority is more about incubating the technologies it will need to meet its own climate objectives — making money is good, too.

“If happens to be that the companies we invest in do well and they become the next Tesla or they return a multiple of our investment, then that’s great. It shows that it’s a validation of what it is, but it’s not the main focus of the fund relative to the broader strategic goal,” Peterson said.

Amazon has previously announced investments in CarbonCure, Pachama, Redwood Materials, Rivian, TurnTide Technologies, BETA Technologies, Ion Energy, and ZeroAvia — bringing the total tally of climate tech start-ups Amazon has invested in to 11. The Fund is still accepting applications for start-ups looking for funding.

There is a growing movement toward companies, foundations and individuals investing in businesses working on new solutions for removing planet-warming pollutants and reducing emissions. That includes Microsoft’s $1 billion Climate Innovation Fund and the Bill Gates-led Breakthrough Energy Venture, as well as the Climate Impact Fund launched by Portland-based VertueLab and Decarbon8-US, or D8, from Seattle’s E8, a network of angel investors.

Bezos in February created his own $10 billion Bezos Earth Fund, which appears less focused on investments in tech companies, but rather will target scientists, activists and non-governmental organizations. Bezos initially said that grants would be announced in the summer, but there is no news yet.

Mike Rea is executive director of E8, a Seattle-based investment network focused on climate tech. He’s being hit with a steady stream of inquiries from potential investors. E8 launched 15 years ago and expects to reach 140 members by the end of the year, a 40% increase over last year. It’s currently raising a new fund while also making $1 million in investments through Decarbon8, a philanthropic funding arm launched just last year.

Scrubbing the Excess CO2 from the Air

Removing CO2 from the atmosphere is one of the challenges which presents the greatest opportunity for technology to intervene in tackling climate change.

The technology, known as direct air capture, or DAC, is a variation on ideas that have been utilized over the course of half a century in submarines and spacecraft: Employ chemical agents to “scrub” the excess CO2 out of the air; dispose of it; then repeat.

Most importantly it is a viable technology. Small plants in mainland Europe have already pulled hundreds of tons of CO2 per year from ambient air.

Plans for larger DAC plants — one in the U.S. Southwest, slated for completion at the end of 2024; another in Scotland, to be finished about a year after the American project — will be built by Carbon Engineering, of British Columbia. Carbon Engineering’s facilities, as initially planned, will be powered by renewable energy and will eventually each remove, on net, about a million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year from the atmosphere.

The most formidable obstacle is cost. Direct Air Capture of Carbon was originally estimated at somewhere between $500 and $600 per ton. A more recent analysis is that an eventual cost range for DAC could be between $94 and $232 per ton. That could be decades away — or it may never come to pass.

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, a U.S. Department of Energy-funded research powerhouse, recently announced a tech breakthrough for carbon capture. Their Eastern Washington scientists have created a carbon dioxide-absorbing solvent that is significantly cheaper to use relative to other options.

The technology is paired with systems that generate CO2, such as coal-fired power plants or in the production of cement or steel. The gas from these facilities flows through a device where it mixes with the solvent, which goes by the acronym EEMPA. The solvent captures the CO2 from the gas. Then the pure CO2 is stripped back out of the EEMPA, which can be reused indefinitely. The CO2 then needs to be stored, most likely in an underground, geologic storage site, or ideally put to another industrial use that keeps it out of the atmosphere.

Currently available commercial technology costs roughly $58 per metric ton of CO2 captured, according to the DOE. The PNNL approach cuts the price to $47, or potentially less. The savings are possible because the solvent’s chemistry is “water lean” so it requires less energy to strip the carbon off of it. And it can be used in a system that’s made of plastic instead of the conventional steel setup, which is another cost savings.

As reported by Lisa Stiffer for GeekWire, the researchers recently published a paper on their findings in the International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control. Next year they’re partnering with the National Carbon Capture Center in Alabama to test the solvent at a larger scale. The longer-term goal is to prove out the technology so that a commercial partner will want to deploy it at scale.

Nori’s Online Marketplace Makes Buying and Selling Carbon Removal More Intuitive

On a different scale, Seattle start-up Nori is building an online marketplace that aims to incentivize individuals and companies to capture carbon from the atmosphere.

It plans to upturn the current economic model that makes it more profitable for companies to emit carbon than to remove it.

“Nori is on a mission to reverse climate change by making it as simple as possible to pay people to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” the company said.

Companies and individuals who want to erase their carbon footprints can buy captured atmospheric carbon via Nori’s marketplace.

Purchasers get certificates to prove they own the carbon and transactions are recorded using blockchain technology. Sellers sign contracts committing them to sequester the carbon for a minimum of ten years.

“If we want people to do something they’re not currently doing, the best way to get them to do it is by paying them,” Nori CEO Paul Gambill

Since its launch in 2017, the company has tried to demystify carbon removal, presenting the element as an exchangeable asset and allowing people to buy and sell it in an intuitive way.

Customers buy Nori Carbon Removal Tonnes (NRTs), which guarantee the removal and storage of one metric tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) for a ten-year period.

The cost of one NRT is currently $15. This is significantly cheaper than buying carbon credits – licences to emit carbon that act as a form of tax on polluters – on emissions trading markets, with the price of EU emissions permits hitting a record price of $50 per tonne last month.

The average American’s carbon footprint is 16 tonnes per year, meaning an individual can use Nori to neutralise their climate impact for an annual investment of $276 (including Nori’s 15 per cent transaction fee). [24×7]