With the verdict on presidential impeachment condoning the incitement of an insurrection that violently attacked the citadel of American democracy, killing at least five people and injuring dozens more, the question of whether political science is, indeed, an oxymoron is on everyone’s mind.

In this essential moment of mindfulness, would you believe that science wins again?

A noted social scientist supported by reams of academic and clinical research, has explained the difference between Republicans and Democrats in neurologlcal terms. It all comes down to pain. In their political and social behavior, the Democrats are shown as stopping short of inflicting actual harm or pain on their fellow citizens, be it through legislation, regulation, public policy or direct political action.

Unless there is no other alternative, the Democrat will refuse to be the cause of suffering. It’s the Utilitarian philosophy, “One for All and All for One,” Gens Una Sumus (”We are One”), the Hippocratic, not the hypocritical, oath. Pain is where the Dems draw the line.

According to the findings cited below, the same cannot be said of Republicans. The studies reveal that R’s do not shrink from inflicting pain on others, including those who are considerably less fortunate than themselves. Call it a lack of empathy, a self-directed focus, a belief that they should be allowed to prosper whenever and however they choose, unhindered by environmental constraints (such as a public health crisis). If their gains come at the expense of other people, so be it.

For Republicans, the pursuit of happiness is neither an inalienable right nor is it a level playing field. Rather it is a contest to be fought and won. A no compromise, zero-sum game. Since the end of the “first” Civil War, the far right wing of one political party has refused to accept the principle that “All men are created equal.”

Capitalism at any Cost?

It is not the dynamics of market forces that are what is attractive about capitalism to Republicans but their ability to exploit those forces by whatever means necessary: Tax reform that disproportionately benefits the very wealthy … Small business Paycheck Protection loans that go to large equity chains… the elimination of health care, food stamps, a better education, and subsidized housing. For a party that does not share a common knowledge nor belief in the science of evolution, the Republican philosophy is decidedly Darwinian.

An Ancient Parable

The classic King Solomon story reads like a Democrat vs. Republican parable. In a kind of Sophie’s Choice B.C., two women appear before the king claiming to be the mother of an infant. One woman is the baby’s actual mother, the other woman intent on obtaining a child tax credit.

The king must decide which woman is the real mother. He proposes a solution: he will draw a sword and divide the baby in half, a pure 50/50 split. Of course, that would take the life of the child, but math is math. The baby’s real mother surrenders. “You take the baby, all of him,” she implores the other woman who is already nodding her consent to split the child in two and divide the benefit. It is the Democrat who is willing to give up her own child if it means no harm will come to him. This also happens to be an analog to the “Baby Moses” story.

More than Anecdotal

What is truly scary about this socio-political divide is that the evidence is more than anecdotal.

The psychology study published in the journal Personality and Individual Differences found that Republicans surveyed had a statistically significant higher level of psychopathology related to boldness and meanness than Democrats. The bibliography below is your reference library to take a deep dive into the research.

Participants in the study completed TriPM, a self-report measure that uses 58 questions to evaluate the three traits that, according to the “triarchic model of psychopathy” make up the disorder: boldness, meanness, and disinhibition.

Test-takers ranked how much they related to various statements like “I’ve injured people to see them in pain” and “I have conned people to get money from them” on a four-point scale of true, somewhat true, somewhat false, and false. The results score test-takers on all three traits of the triarchic model.

The researchers found that psychopathic boldness and meanness tended to be higher in Republicans compared to Democrats. Disinhibition was not related to political affiliation.

Mean Girls and Mean Boys

In other words, Republicans were more likely to agree with statements such as “I don’t mind if someone I dislike gets hurt”, “I taunt people just to stir things up,” “I can get over things that would traumatize others,” and “I never worry about making a fool of myself with others.”

The researchers also found that boldness was associated with conservative opinions on economic issues, while meanness was associated with conservative opinions on social issues. Boldness was linked to opposition to government spending, immigration, and gay rights. Meanness was associated with opposition to universal healthcare, marijuana legalization, equal pay for women, and affirmative action.

How Many Must Die?

The acute differences in sentiment are laid bare in the Coronavirus pandemic which has taken the lives of half-a-millon people in this country and infected many more millions of Americans. The de-installed Republican establishment not only downplayed the overall impact of the virus from the outset but expressed disdain, if not disgust, for the face coverings and social distancing that have been mandated as the first line of defense against it.

At the ill-fated, super-spreader events, also known as Republican presidential campaign rallies, face masks were scarcely seen, and in so-called “red states,” the notion was flaunted. The irrational politicization of the public health infestation placed millions of people at risk and can only be explained by a pathological lack of concern for others. In the criminal code, it goes beyond criminal neglect and is referred to as depraved indifference.

Ideological differences between political partisans have been attributed to logical, psychological, and social constraints and past scholarship has focused primarily on institutional political processes or individual policy preferences, rather than biological differences in evaluative processes.

However, in the study, “Psychopathic traits and politics: Examining affiliation, support of political issues, and the role of empathy,“ authored by Olivia C. Preston and Joye C. Anestis, the work revealed physiological correlations of the different responses by liberals and conservatives.

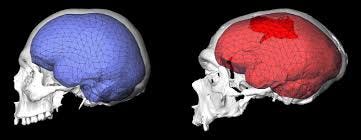

At the London Institute, additional research conducted with young adults by neuroscientist Ryoto Kanai and colleagues examined four brain regions: the right amygdala, left insula, right entorhinal cortex, and anterior cingulate (ACC). Incredibly, the brain responses in these sectors indicated measurable differences in liberals and conservatives providing further evidence that political ideology might be connected to differences in cognitive processes.

The longstanding traditional model in political science, which uses the party affiliation of a person’s mother and father to predict the child’s affiliation, is only accurate about 69.5% of the time. The model based on the differences in brain structure distinguishes liberals from conservatives with 71.6% accuracy.

Writing in Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans, Dr. Darren Schreiber, a researcher in neuropolitics at the University of Exeter, has concluded that “The ability to accurately predict party politics using only brain activity suggests that investigating basic neural differences between voters may provide us with more powerful insights than the traditional tools of political science.” The findings also prove to work in reverse: while genetics or parental influence may play a significant role in political party affiliations, being a Republican or Democrat changes how the brain functions.

Supporting Documentation

References

1. Jost JT, Glaser J, Kruglanski AW, Sulloway FJ (2003) Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin 129: 339–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Kam CD, Simas EN (2010) Risk orientations and policy frames. The Journal of Politics 72: 381–396. [Google Scholar]

3. Jost JT (2006) The end of the end of ideology. Am Psychol 61: 651–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Converse P (1964) The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics. In: Apter D, editor. Ideology and Discontent. New York: Free Press. 206–261.

5. Oxley DR, Smith KB, Alford JR, Hibbing MV, Miller JL, et al. (2008) Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science 321: 1667–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Amodio DM, Jost JT, Master SL, Yee CM (2007) Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism. Nat Neurosci 10: 1246–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Fellows LK (2004) The cognitive neuroscience of human decision making: a review and conceptual framework. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 3: 159–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Schonberg T, Fox CR, Poldrack RA (2011) Mind the gap: bridging economic and naturalistic risk-taking with cognitive neuroscience. Trends Cogn Sci 15: 11–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Slovic P (2000) The perception of risk. London; Sterling, VA: Earthscan Publications. xxxvii, 473 p. p.

10. Bechara A (2001) Neurobiology of decision-making: risk and reward. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 6: 205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Knutson B, Greer SM (2008) Anticipatory affect: neural correlates and consequences for choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363: 3771–3786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Vorhold V (2008) The neuronal substrate of risky choice: an insight into the contributions of neuroimaging to the understanding of theories on decision making under risk. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1128: 41–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Lang PJ, Cuthbert BN (1984) Affective information processing and the assessment of anxiety. J Behav Assess 6: 369–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Mogg K, Mathews A, Weinman J (1989) Selective processing of threat cues in anxiety states: a replication. Behav Res Ther 27: 317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Kanai R, Feilden T, Firth C, Rees G (2011) Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults. Current biology 21: 677–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR (2003) Role of the amygdala in decision-making. Amygdala in Brain Function: Bacic and Clinical Approaches 985: 356–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Levine DS (2009) Brain pathways for cognitive-emotional decision making in the human animal. Neural Networks 22: 286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Morrison SE, Salzman CD (2010) Re-valuing the amygdala. Curr Opin Neurobiol 20: 221–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Craig ADB (2011) Significance of the insula for the evolution of human awareness of feelings from the body. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1225: 72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Critchley HD (2005) Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. J Comp Neurol 493: 154–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Botvinick MM (2007) Conflict monitoring and decision making: reconciling two perspectives on anterior cingulate function. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 7: 356–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, Carter CS (2004) Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends Cogn Sci 8: 539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Abramowitz A, Saunders K (1998) Ideological Realignment in the U.S. Electorate. Journal of Politics 60: 634–652. [Google Scholar]

24. Abramowitz AI, Saunders KL (2008) Is polarization a myth? Journal of Politics 70: 542–555. [Google Scholar]

25. Jacobson GC (2004) Partisan and Ideological Polarization in the California Electorate. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 4: 113–139. [Google Scholar]

26. Paulus MP, Rogalsky C, Simmons A, Feinstein JS, Stein MB (2003) Increased activation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism. Neuroimage 19: 1439–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Arce E, Miller DA, Feinstein JS, Stein MB, Paulus MP (2006) Lorazepam dose-dependently decreases risk-taking related activation in limbic areas. Psychopharmacology 189: 105–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Paulus MP, Hozack N, Frank L, Brown GG, Schuckit MA (2003) Decision making by methamphetamine-dependent subjects is associated with error-rate-independent decrease in prefrontal and parietal activation. Biol Psychiatry 53: 65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lieberman M, Schreiber D, Ochsner K (2003) Is Political Sophistication Like Learning to Ride a Bicycle? How Cognitive Neuroscience Can Inform Research on Political Thinking. Political Psychology 24: 681–704. [Google Scholar]

30. Sarinopoulos I, Grupe DW, Mackiewicz KL, Herrington JD, Lor M, et al. (2010) Uncertainty during anticipation modulates neural responses to aversion in human insula and amygdala. Cereb Cortex 20: 929–940. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Gallagher M, Holland PC (1994) The amygdala complex: multiple roles in associative learning and attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91: 11771–11776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Buchel C, Morris J, Dolan RJ, Friston KJ (1998) Brain systems mediating aversive conditioning: an event-related fMRI study. Neuron 20: 947–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. LeDoux JE (1992) Brain mechanisms of emotion and emotional learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2: 191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Breiter HC, Rosen BR (1999) Functional magnetic resonance imaging of brain reward circuitry in the human. Ann N Y Acad Sci 877: 523–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Canli T, Zhao Z, Brewer J, Gabrieli JD, Cahill L (2000) Event-related activation in the human amygdala associates with later memory for individual emotional experience. J Neurosci 20: RC99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Ernst M, Bolla K, Mouratidis M, Contoreggi C, Matochik JA, et al. (2002) Decision-making in a risk-taking task: a PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology 26: 682–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Garavan H, Pendergrass JC, Ross TJ, Stein EA, Risinger RC (2001) Amygdala response to both positively and negatively valenced stimuli. Neuroreport 12: 2779–2783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Gottfried JA, O’Doherty J, Dolan RJ (2002) Appetitive and aversive olfactory learning in humans studied using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 22: 10829–10837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Tracey I, Becerra L, Chang I, Breiter H, Jenkins L, et al. (2000) Noxious hot and cold stimulation produce common patterns of brain activation in humans: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett 288: 159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ (2004) Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci 7: 189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Phan KL, Wager T, Taylor SF, Liberzon I (2002) Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage 16: 331–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Huettel SA, Misiurek J, Jurkowski AJ, McCarthy G (2004) Dynamic and strategic aspects of executive processing. Brain Res 1000: 78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD (2003) Does rejection hurt? An FMRI study of social exclusion. Science 302: 290–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Craig AD (2002) How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci 3: 655–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Saxe R, Kanwisher N (2003) People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. Neuroimage 19: 1835–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Van Overwalle F (2009) Social cognition and the brain: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 829–858. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Poole KT (2005) Spatial models of parliamentary voting. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. xviii, 230 p.

48. Alford JR, Funk CL, Hibbing JR (2005) Are Political Orientations Genetically Transmitted? American Political Science Review 99: 153–167. [Google Scholar]

49. Achen C (2002) Parental socialization and rational party identification. Political Behavior 24: 151–170. [Google Scholar]

50. Draganski B, Gaser C, Busch V, Schuierer G, Bogdahn U, et al. (2004) Neuroplasticity: changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature 427: 311–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Scholz J, Klein MC, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H (2009) Training induces changes in white-matter architecture. Nat Neurosci. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

52. Woollett K, Maguire EA (2011) Acquiring “the Knowledge” of London’s Layout Drives Structural Brain Changes. Current biology. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

53. Settle JE, Dawes CT, Fowler JH (2009) The Heritability of Partisan Attachment. Political Research Quarterly 62: 601–613. [Google Scholar]

54. Fowler JH, Schreiber D (2008) Biology, politics, and the emerging science of human nature. Science 322: 912–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Cox RW (1996) AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 29: 162–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Boynton GM, Engel SA, Glover GH, Heeger DJ (1996) Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci 16: 4207–4221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Lancaster JL, Woldorff MG, Parsons LM, Liotti M, Freitas CS, et al. (2000) Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp 10: 120–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Articles from PLoS ONE are provided here courtesy of Public Library of Science

Formats:Darren Schreiber, Greg Fonzo, Alan N. Simmons, Christopher T. Dawes, Taru Flagan, James H. Fowler, Martin P. Paulus. Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8 (2): e52970 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052970