When Henry Ford ushered in the world of mass production at the turn of the century, making the automobile available to the middle and working classes, he reshaped the culture of America forever.

As Model-T cars rolled off the factory floor, few (if any) newly minted “motorists” stopped to ask whether the fossil fuels that powered the vehicles would set America on a calamitous course to air pollution and climate crises.

When jet airplanes took to the skies and multiplied the environmental impact of fuel-burning, no protestors sought to ground the aircraft on the basis of energy consumption. Both technologies spun-up the gears of travel and commerce, changing the course of history.

Now it is the tremendous energy requirements necessary to process blockchain transactions, demanded by the redundant backups of a decentralized system, and compounded by the challenge to validate the integrity of each independent blockchain node, that are complicating the future of cryptocurrency. Is there a silver lining to what could one day become the new gold standard?

The new Seattle NFT Museum in Belltown is celebrating digital art as a world showcase for unique, artistic NFTs, while just down the road, Climate Pledge Arena seeks to become the first “zero carbon footprint” stadium in America. Are these two sides of the same ecological Bitcoin?

No one knows exactly how much power is used to create (or mine) cryptocurrency transactions, but it is staggering. Estimates range from the amount of power used by Finland each year, to that used by Brazil. An authoritative source, the University of Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index, calculates total consumption at over 80 GwH, or the equivalent of 23 coal fired power stations.

That is a huge amount of power for relatively few crypto users and miners. And the more people that mine crypto, the more power is required. It currently costs between USD $7-$11,000 of electricity to mine one bitcoin. But because they sell for much more, there is every incentive to carry on mining and pay the power costs.

A Signalling of Virtue

The virtuous signal from crypto investors is that it is building a better, more democratic, financial infrastructure that is P2P (Peer-to-Peer), pseudonymous, without banking fees, and one that is both mobile and secure. Granted, this better infrastructure is provided by the Internet and blockchain, neither of which are exclusive to or because of crypto.

So what is it about crypto and the current excitement over the digital asset called an NFT that balances the other side of the ledger? Can we celebrate the digital art, but not the science?

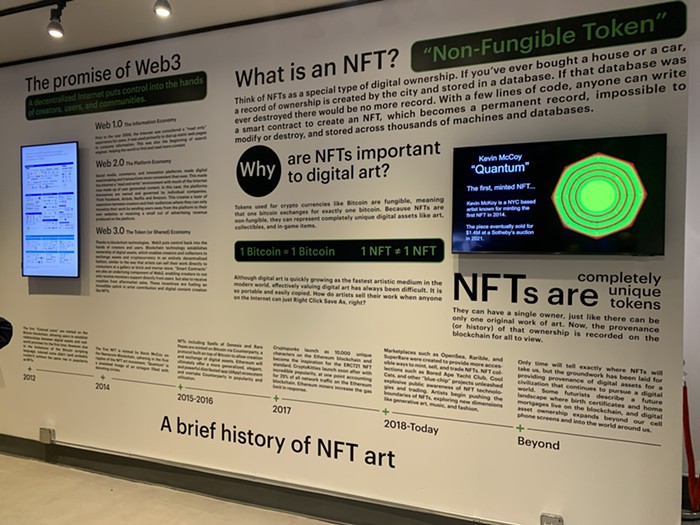

Essentially an NFT is a one-of-a-kind digital file — it could be a photo or a song or Jack Dorsey’s first-ever Tweet. When two cryptocurrency exchange employees got married they turned their wedding ring into an NFT by making it a part of the Blockchain.

Mostly, what people think of as an NFT are actually the digital files, but that is not what an NFT actually is. The NFT is the record on the blockchain that stores the information about the digital file — who created it, who linked it to the blockchain, and then who bought it and who has owned it throughout its history. That is what the actual NFT is.

NFT stands for “non-fungible token,” and it can technically contain anything digital, including drawings, animated GIFs, songs, or items in video games. An NFT can either be one-of-a-kind, like a real-life painting, or one copy of many, like trading cards. The blockchain keeps track of who has ownership of the file.

While we are all accustomed to thinking about digital goods as virtual or ethereal, the “cost” of manufacturing an NFT is steep. Take “Space Cat,” an NFT that’s basically a GIF of a cat in a rocket heading to the Moon. Space Cat’s carbon footprint is equivalent to an EU resident’s electricity usage for two months, according to the website Cryptoart.wtf.

The Cryptotart site used to let people click through the estimated greenhouse gas emissions associated with individual NFTs until creator Memo Akten took it down on March 12th. Akten, a digital artist, had analyzed 18,000 NFTs and found that the average NFT has a carbon footprint somewhat lower than Space Cat’s but still equivalent to more than a month’s worth of electricity for a person living in the EU. Those numbers were shocking to some people. But then Akten saw that the website had been used to wrongly attribute an NFT marketplace’s emissions to a single NFT. He took the site offline after he discovered that it “has been used as a tool for abuse and harassment,” according to a note posted on the site.

“The imagination of NFT artists and creators is thrilling. We wanted to create a space to serve the NFT community while helping put Seattle on the map as a hub for NFT and Blockchain innovation. We’re not experts, and we’re here to learn as much as anyone. That is why we are counting on the feedback and support of NFT enthusiasts to continue growing the vision.” “

– Jennifer Wong, Co-Founder Seattle NFT Museum

Bitcoin Raises the Stakes

To keep cryptocurrency insulated and safe, Bitcoin was designed to make participation in the network expensive: computers that upkeep the ledger, also called mining nodes, are required to constantly try to crack daunting mathematical puzzles, receiving Bitcoin rewards upon solving them. In so doing, these (fairly expensive) computers consume a lot of electricity, a set-up intended to render attempts to tamper with the Bitcoin ledger too onerous and encourage cooperation instead.

Since the crypto art craze is pretty new, none of the data that’s out there so far has been reviewed by outside experts. One thing that has cast a wary eye is that NFTs are largely bought and sold in marketplaces like Nifty Gateway and SuperRare that use the cryptocurrency Ethereum. Ethereum, like most major cryptocurrencies, is built on a system called “proof of work” that is incredibly energy hungry. There’s a fee associated with making a transaction on Ethereum — and, ironically, that fee is called “gas.”

Proof of work acts as a sort of security system for cryptocurrencies like Ethereum and bitcoin since there’s no third party, like a bank, that oversees transactions. To keep financial records secure, the system forces people to solve complex puzzles using energy-guzzling machines. Solving the puzzles lets users, or “miners,” add a new “block” of verified transactions to a decentralized ledger called the blockchain. The miner then gets new tokens or transaction fees as a reward. The process is incredibly energy inefficient on purpose.

The idea is that using up inordinate amounts of electricity — and probably paying a lot for it — makes it less profitable for someone to muck up the ledger. As a result, Ethereum uses about as much electricity as the entire country of Libya.

Can Proof of Work Evolve to Proof of Stake?

There are other strategies for keeping a blockchain secure that might not be as hard on the planet. The most popular alternative to proof of work is a system called “proof of stake.”NBA’s Top Shot, the marketplace where basketball fans can buy NBA highlights as NFTs, operates on the Flow blockchain, which is an example of an arguably more centralized blockchain running on the proof-of-stake model.

This system still requires users to have some kind of skin in the game to dissuade bad behavior. But instead of having to pay for huge amounts of electricity to enter the game, they instead have to lock up some of their own cryptocurrency tokens in the network to “prove” they’ve got a “stake” in keeping the ledger accurate. If they get caught doing anything fishy, they’ll be penalized by losing those tokens. That gets rid of the need for computers to solve complex puzzles, which, in turn, gets rid of emissions.

Ethereum has said for years that it will eventually switch to proof of stake. That’s what crypto art optimists are hoping for.

“That would essentially mean that Ethereum’s electricity consumption will literally over a day or overnight drop to almost zero,” says Michel Rauchs, a research affiliate at the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

The problem is that people have been waiting for years for Ethereum to make the change, and some are skeptical that it ever will. First, Ethereum will have to convince everyone that proof of stake is the way to go. Otherwise, the whole system could collapse.

“If not everyone agrees to that change, you’re going to be in a situation where the network just falls apart,” says economist Alex de Vries. “It can literally break into multiple chains if not everyone runs the same software. That’s the downside of trying to upgrade public blockchains like Ethereum.”

Other Promising Approaches

Private blockchains do exist, and some, like Flow, are completely devoted to NFT transactions, allowing them to sidestep some of the issues with cryptocurrencies like Ethereum. But those kinds of blockchains move away from what cryptocurrencies were supposed to do in the first place, which is create a decentralized network where anyone can make transactions without the oversight of a single institution.

There are other ways to bring down emissions from NFTs and keep a more decentralized proof-of-work network. One potential solution is to build out another “layer” on top of the existing blockchain. Working on this second layer can save energy because transactions happen “off-chain” — away from the energy-intensive proof-of-work process.

For example, two people who want to trade NFTs might open up their own “channel” on the second layer where they can make a virtually unlimited number of transactions. Once they’re done doing business, they can settle up the net result of their transactions back on the blockchain, where it can be added to the verified ledger via the proof-of-work process. You’re essentially bundling or netting a whole bunch of transactions into just a few that need to take place on the inefficient blockchain, which ultimately saves energy. The bitcoin Lightning Network, launched in 2018, is an early example of a “second layer.”

The Amazon.com of NFTs

The Amazon.com wannabe of the NFT is OpenSea at opensea.io. More or less, they have become the de facto NFT marketplace. Why? Other marketplaces have tended to follow the art gallery type of model. You go there because you like the particular type of products they have curated. OpenSea wants to provide a representation of everything that’s out there, everything on the blockchain. If it’s on OpenSea you can also use special ordering tools.

While there is no guarantee of the worthiness of OpenSea items, it is the easiest place to buy and sell NFTs. “They are the casino where all of these bets on NFTS are happening,” says Russell Brandom, Policy Editor for The Verge.

In this case, the open sea is not without squalls or riptides. “I don’t know that there are security-centered issues, per say, with OpenSea,” says Brandom, “but [like any new technology], there have been moderation issues in a very chaotic marketplace that, because OpenSea is kind of the broker of record, they end up at the center of it.”

Buyers Place Your Bets

All of the potential fixes to the climate pollution problem of NFTs are in the works to varying degrees, but they haven’t been widely adopted yet. Still, a lot of artists — and even some environmentalists — are optimistic about crypto art.

Ultimately, artists are the ones pushing the most for change. If marketplaces for NFTs don’t start to meet their demands, artists could start minting their NFTs on marketplaces using cleaner cryptocurrencies. There’s already an artist-led effort to raise money to reward people who can figure out new ways to make crypto art more sustainable. Anyone who wants to support those artists by buying their work can migrate along with them to less polluting platforms — or maybe just buy a physical copy of their work.

Is betting on crypto to move beyond hyped-up pictures of “bored apes” a good idea? Russell Brandom isn’t too sure.

“Put it this way — for any specific use case, the case for NFTs is pretty weak, like I’m not convinced it will take off in this particular area. But will it take off for something? Will we find some reason or some thing that this stuff is useful for? I’m a little more credulous about that. Where we have all these people looking for something that this will be good for, and there’s a ton of hype and a ton of energy, well, hopefully they find something, at some point. I don’t know if I want to bet on that, but it’s at least plausible to me.”

In the meantime, we’re bound to see people splurging on digital goods for months and years to come. [24×7]